Physical World/Geology and Physical Geography

Volcanoes

Black smoker – (or sea vent) is a type of hydrothermal vent found on the ocean floor. Formed when superheated water from below Earth’s crust comes through the ocean floor. This water is rich in dissolved minerals from the crust, most notably sulphides. When it comes in contact with cold ocean water, many minerals precipitate, forming a black chimney-like structure around each vent

Crater lake – a lake that forms in a volcanic crater or caldera

Cumulate rocks – igneous rocks formed by the accumulation of crystals from a magma either by settling or floating

Diapir – a type of intrusion in which a more mobile and ductily deformable material is forced into brittle overlying rocks

Effusive eruption – a volcanic eruption characterized by the outpouring of lava onto the ground (as opposed to the violent fragmentation of magma by explosive eruptions)

Eruptions – there are three different metatypes of eruptions. The most well-observed are magmatic eruptions, which involve the decompression of gas within magma that propels it forward. Phreatomagmatic eruptions are another type of volcanic eruption, driven by the compression of gas within magma, the direct opposite of the process powering magmatic activity. The last eruptive metatype is the Phreatic eruption, which occurs when magma heats ground or surface water. The extreme temperature of the magma causes near-instantaneous evaporation to steam; these three eruptive types often exhibit no magmatic release, instead causing the granulation of existing rock

Types of magmatic eruption – Hawaiian, Strombolian, Vulcanian, Pelean, and Plinian

Types of phreatomagmatic eruption – Surtsetyan, Submarine, Subglacial

Extrusive – refers to the mode of igneous volcanic rock formation in which hot magma from inside the Earth flows out (extrudes) onto the surface as lava or explodes violently into the atmosphere to fall back as pyroclastics or tuff. This is opposed to intrusive rock formation, in which magma does not reach the surface

Hot spot – a portion of the Earth's surface that may be far from tectonic plate boundaries and that experiences volcanism due to a rising mantle plume, e.g. under Kilawea in Hawaii

Hydrothermal vent – a fissure in a planet's surface from which geothermally heated water issues. Hydrothermal vents are commonly found near volcanically active places

Intrusion – liquid rock that forms under the surface of the earth

Intrusive rock – an igneous rock formed by the entrance of magma into preexisting rock

Lahar – a type of mudflow composed of pyroclastic material and water that flows down from a volcano, typically along a river valley

Lava – the molten rock expelled by a volcano during an eruption and the resulting rock after solidification and cooling

Lava lakes – large volumes of molten lava, usually basaltic, contained in a volcanic vent, crater. There are only five persistent lava lakes: Erta Ale (Ethiopia), Ambrym (Vanuatu), Mount Erebus (Ross Island, Antarctica), Kilauea (Big Island, Hawaii), Mount Nyiragongo (Democratic Republic of the Congo)

Magma chamber – a large underground pool of liquid rock found beneath the surface of the Earth

Mantle plume – a thermal abnormality where hot rock nucleates at the core-mantle boundary and rises through the Earth's mantle becoming a diapir in the Earth's crust

Mud volcano – formations created by geo-excreted liquids and gases, although there are several different processes which may cause such activity

Pillow lavas – lavas that contain characteristic pillow-shaped structures that are attributed to the extrusion of the lava under water, or subaqueous extrusion

Pyroclastic flow – a fast-moving current of superheated gas and rock (collectively known as tephra). Pyroclastic flow is also known as a pyroclastic density current

Shield volcano – a large volcano with shallowly-sloping sides

Stratovolcano – a tall, conical volcano composed of many layers of hardened lava, tephra, and volcanic ash. These volcanoes are characterized by a steep profile and periodic, explosive eruptions. Also called a composite volcano

Superplume – a very large mantle plume

Tephra – air-fall material produced by a volcanic eruption regardless of composition or fragment size

Tuff – a type of rock consisting of consolidated volcanic ash ejected from vents during a volcanic eruption

VEI – Volcanic Explosivity Index, was devised by Chris Newhall of the U.S. Geological Survey and Steve Self at the University of Hawaii in 1982 to provide a relative measure of the explosiveness of volcanic eruptions. The scale is logarithmic and open-ended with the largest volcanoes in history given magnitude 8

Volcanic bomb – a mass of molten rock (tephra) larger than 64 mm in diameter, formed when a volcano ejects viscous fragments of lava during an eruption. They cool into solid fragments before they reach the ground. Bombs are named according to their shape, e.g. spindle, breadcrust, ribbon

Last super-eruption – Toba, on Sumatra 74,000 years ago

Biggest volcanic eruption in recorded history – Tambora, Indonesia in 1815. Led to ‘The year with no summer’ in 1816

Earthquakes

Hypocentre – the position where the strain energy stored in the rock is first released, marking the point where the fault begins to rupture. This occurs at the focal depth below the epicentre

Liquefaction – earthquakes can cause liquefaction where loosely packed, water-logged sediments come loose from the intense shaking of the earthquake

Love waves – (also known as Q waves) are surface seismic waves that cause horizontal shifting of the earth during an earthquake. A. E. H. Love predicted the existence of Love waves mathematically in 1911

Megathrust earthquakes – occur at subduction zones at destructive plate boundaries. The 2004 Pacific Ocean tsunami was caused by a megathrust earthquake

Mercalli scale – measures intensity of earthquakes

Moment magnitude scale (MMS) – measures the size of earthquakes in terms of the energy released. Developed to succeed the Richter scale

Rayleigh waves – a type of surface acoustic wave that travels on solids. They are produced on the Earth by earthquakes, in which case they are also known as ‘ground roll’

Richter magnitude scale – measures energy contained in an earthquake. Richter scale is a base-10 logarithmic scale, which defines magnitude as the logarithm of the ratio of the amplitude of the seismic waves to an arbitrary, minor amplitude

Seismic waves – two types; body wave and surface waves

Body waves travel through the interior of the Earth

P-wave – primary wave or pressure wave (body wave)

S-wave – secondary wave or shear wave (body wave)

Surface waves (L-waves) are analogous to water waves and travel along the Earth's surface

Shadow zone – an area of the Earth's surface where seismographs cannot detect an earthquake after its seismic waves have passed through the Earth

One of the most devastating earthquakes in recorded history was the 1556 Shaanxi earthquake, which occurred in 1556 in Shaanxi province, China. More than 830,000 people died

The 1960 Chilean Earthquake is the largest earthquake that has been measured on a seismograph, reaching 9.5 magnitude in1960. The energy released was approximately twice that of the next most powerful earthquake, the Good Friday Earthquake of 1964 which was centered in Prince William Sound, Alaska

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake caused devastating fires to break out in the city that lasted for several days. As a result, about 3,000 people died and over 80% of San Francisco was destroyed

Meteorology and climatology

Earth’s atmosphere

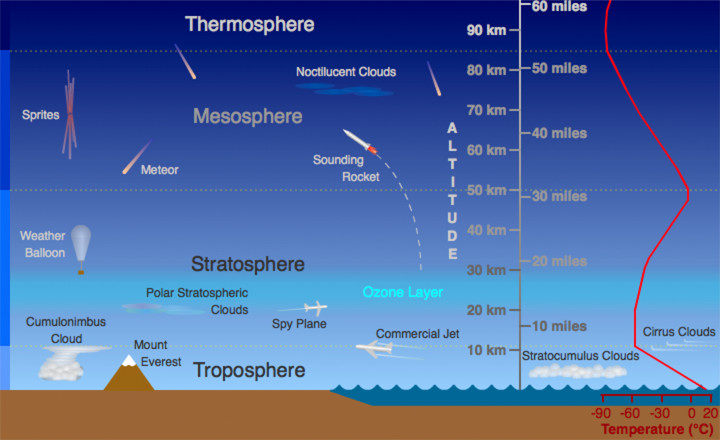

Troposphere – the lowest portion of Earth's atmosphere. It contains approximately 75% of the atmosphere's mass and 99% of its water vapour and aerosols. The average depth of the troposphere is approximately 17 km in the middle latitudes

Tropopause – the boundary region between the troposphere and the stratosphere. The tropopause is an inversion layer. The environmental lapse rate changes from positive, as it behaves in the troposphere, to the stratospheric negative one

Stratosphere – is stratified in temperature, with warmer layers higher up and cooler layers farther down. The stratosphere is situated between about 10 km and 50 km altitude above the surface at moderate latitudes. Contains the ozone layer

Stratopause – the boundary region between the stratosphere and the mesosphere

Mesosphere – is located about 50 to 85 km above the Earth's surface

Mesopause – the boundary region between the mesosphere and the thermosphere

Thermosphere – begins about 80 km above the earth. Within this layer, ultraviolet radiation causes ionization. Thermospheric temperatures increase with altitude due to absorption of highly energetic solar radiation by the small amount of residual oxygen still present

Karman line lies at an altitude of 100 km above the Earth's sea level, and commonly represents the boundary between the Earth's atmosphere and outer space. It lies within the thermosphere

Thermopause – the atmospheric boundary of Earth's energy system, located at the top of the thermosphere. The exact altitude varies by the energy inputs of location, time of day, solar flux, season, etc. and can be between 500–1000 km high at a given place and time

Exosphere – the uppermost layer of the atmosphere. The exosphere is sometimes considered a part of outer space

Ionosphere – a part of the upper atmosphere, comprising portions of the mesosphere, thermosphere and exosphere, distinguished because it is ionized by solar radiation. It plays an important part in atmospheric electricity and forms the inner edge of the magnetosphere. It has practical importance because, among other functions, it influences radio propagation to distant places on the Earth. Divided in to D, E, Es (sporadic) and F layers

The F region of the ionosphere is home to the F layer of ionization, also called the Appleton layer, after the English physicist Edward Appleton. As with other ionospheric sectors, 'layer' implies a concentration of plasma, while 'region' is the area that contains the said layer. The F region contains ionized gases at a height of around 150–800 km above sea level, placing it in the Earth’s thermosphere

Total electron content (TEC) – the total number of electrons present along a path between two points in the ionosphere. Scientists have observed anomalies in the TEC of the upper atmosphere just before an earthquake. These anomalies are noted via disruptions in GPS

Atmosphere – nitrogen 78.1%, oxygen 21%, argon 0.9%, carbon dioxide 0.03%

Ozone layer – a layer in the stratosphere (at approximately 20 miles) that contains a concentration of ozone (O3) sufficient to block most ultraviolet radiation. It is destroyed by the reaction with atomic oxygen, which is catalyzed by the presence of certain free radicals, of which the most important are hydroxyl (OH), nitric oxide (NO) and atomic chlorine (Cl) and bromine (Br)

Dobson unit – a unit of measurement of atmospheric ozone

Lapse rate – the rate at which atmospheric temperature decreases with increase in altitude

The main jet streams are located near the tropopause, the transition between the troposphere (where temperature decreases with height) and the stratosphere (where temperature increases with height). The major jet streams on Earth are westerly winds

William Ferrel developed theories which explained the mid-latitude atmospheric circulation cell in detail, and it is after him that the Ferrel cell is named

There are three primary circulation cells. They are known as the Hadley cell, Ferrel cell, and Polar cell

Hadley cell is a tropical atmospheric circulation that is defined by the average over longitude, which features rising motion near the equator, poleward flow 10-15 kilometers above the surface, descending motion in the subtropics, and equatorward flow near the surface

Ferrel cell is a secondary circulation feature, dependent for its existence upon the Hadley cell and the Polar cell. It is sometimes known as the ‘zone of mixing’

Polar cell – warm air rises at lower latitudes and moves poleward through the upper troposphere at both the north and south poles. When the air reaches the polar areas, it has cooled considerably, and descends as a cold, dry high pressure area, moving away from the pole along the surface but twisting westward as a result of the Coriolis effect to produce the Polar easterlies

On clear, calm nights, radiational cooling results in a temperature increase with height. In this situation, known as a nocturnal inversion, turbulence is suppressed by the strong thermal stratification

Isohel – a line of equal or constant solar radiation

Clouds

Nephology – study of clouds

Isoneph – a line representing points of equal amounts of cloud cover

Luke Howard proposed a nomenclature system for clouds, in 1802. He named the three principal categories of clouds – cumulus, stratus, and cirrus

Ceilometer – a device used to determine the height of a cloud base

Low clouds – stratus (St), cumulonimbus (Cb), cumulus (Cu), stratocumulus (Sc)

Medium clouds – nimbostratus (Ns), altocumulus (Ac), altostratus (As)

High clouds – cirrus (Ci), cirrocumulus (Cc), cirrostratus (Cs)

Pyrocumulus cloud is produced by the intense heating of the air from the surface and the convection it causes, usually in the presence of heavy moisture. Phenomena such as a volcanic eruption, forest fire or industrial activities can induce formation of this cloud

Undulatus asperatus (or asperatus) is a rare, newly recognized cloud formation that was proposed in 2009 as the first cloud formation added since cirrus intortus in 1951 to the International Cloud Atlas of the World Meteorological Organization

Pileus, also called scarf cloud or cap cloud, is a small, horizontal cloud that can appear above a cumulus or cumulonimbus cloud

Night clouds or noctilucent clouds are tenuous cloud-like phenomena that are the ‘ragged-edge’ of a much brighter and pervasive polar cloud layer called polar mesospheric clouds in the upper atmosphere, visible in a deep twilight

Arcus cloud is a low, horizontal cloud formation

Shelf cloud is a low, horizontal, wedge-shaped arcus cloud. A shelf cloud is attached to the base of the parent cloud, which is usually a thunderstorm, but could form on any type of convective clouds

Roll cloud is a low, horizontal, tube-shaped, and relatively rare type of arcus cloud. They differ from shelf clouds by being completely detached from other cloud features

Cloud iridescence – the occurrence of colours in a cloud similar to those seen in oil films on puddles. The colours are usually pastels

Wind

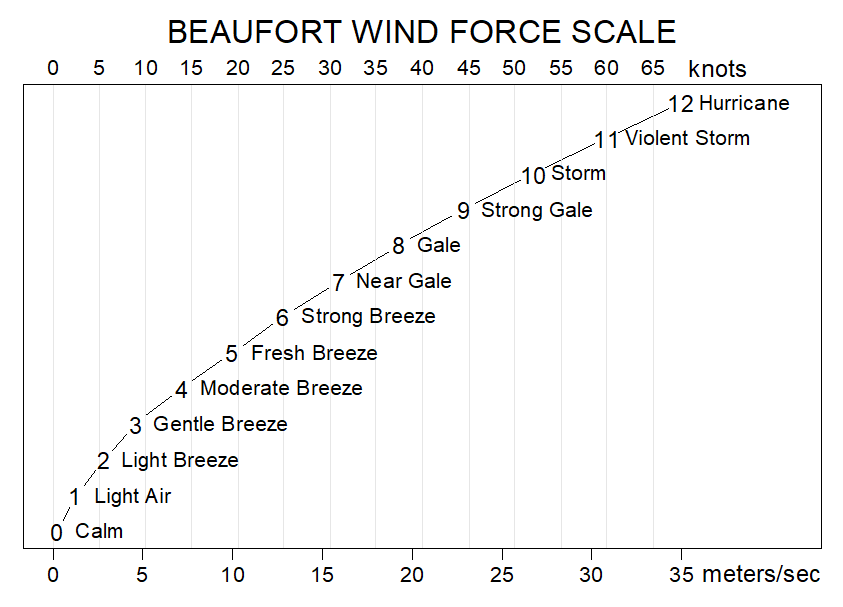

Beaufort wind force scale was devised in 1805 by Royal Navy officer Francis Beaufort

Helm wind – a named wind in Cumbria, a north-easterly wind which blows down the south-west slope of the Cross Fell escarpment. It is the only named wind in the British Isles

Harmattan – a cold-dry and dusty trade wind. This northeasterly wind blows from the Sahara Desert into the Gulf of Guinea during the winter

Khamsin – wind that blows in North Africa. From Arabic for ‘fifty’, as it blows for 50 days

Mistral – a strong, cold and northwesterly wind that blows down the Rhone from southern France into the northern Mediterranean

Chinook winds – foehn winds in the interior West of North America, where the Canadian Prairies and Great Plains meet various mountain ranges

Brickfielder – a hot and dry wind in the desert of Southern Australia that occurs in the summer season

Cape Doctor –a strong, persistent and dry south-easterly wind that blows on the South African coast from spring to late summer

Fremantle Doctor – the cooling afternoon sea breeze which occurs during summer months in south west coastal areas of Western Australia

Sirocco – a Mediterranean wind that comes from the Sahara

Foehn wind – a type of dry down-slope wind that occurs in the lee (downwind side) of a mountain range

Derecho – (Spanish: ‘straight’), is a widespread and long-lived, violent convectively induced straight-line windstorm that is associated with a fast-moving band of severe thunderstorms in the form of a squall line usually taking the form of a bow echo

Isotach – a line representing points of equal wind speed

Katabatic wind – blows down a topographic incline such as a hill, mountain, or glacier

Anabatic wind – blows up a steep slope or mountain side

Horse latitudes are subtropical latitudes between 30 and 35 degrees both north and south. This region is an area of variable winds mixed with calm

Trade winds are the prevailing pattern of easterly surface winds found in the tropics, within the lower portion of the Earth's atmosphere, in the lower section of the troposphere near the Earth's equator

Monsoon – a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by seasonal changes in precipitation

Typhoon – a mature tropical cyclone that develops in the western part of the North Pacific Ocean

Ridge lift (or 'slope lift') is created when a wind strikes an obstacle, usually a mountain ridge or cliff, which is large and steep enough to deflect the wind upward

Polar vortex – a persistent, large-scale cyclone located near one or both of a planet's geographical poles

Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale (SSHWS) classifies hurricanes into five categories distinguished by the intensities of their sustained winds. To be classified as a hurricane, a tropical cyclone must have maximum sustained winds of at least 74 mph (Category 1). The highest classification in the scale, Category 5, is reserved for storms with winds exceeding 156 mph

The Hurricane of 1900 made landfall in the city of Galveston, Texas. It had estimated winds of 145 miles per hour at landfall, making it a Category 4 storm on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale. It was the deadliest hurricane in US history

Hurricane Katrina was the costliest natural disaster, as well as one of the five deadliest hurricanes, in the history of the United States. Katrina caused severe destruction along the Gulf coast from central Florida to Texas in 2005, much of it due to the storm surge. The most significant number of deaths occurred in New Orleans, which flooded as the levee system catastrophically failed

Enhanced Fujita scale (EF scale) rates the strength of tornadoes in the United States and Canada based on the damage they cause. Implemented in place of the Fujita scale introduced in 1971, it began operational use in the United States in 2007, followed by Canada in 2013. The scale has the same basic design as the original Fujita scale: six categories from zero to five representing increasing degrees of damage. It was revised to reflect better examinations of tornado damage surveys. EF5 has an estimated wind speed in excess of 200 mph

The most record-breaking tornado in recorded history was the Tri-State Tornado, which roared through parts of Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana in 1925

The deadliest tornado in world history was the Daultipur-Salturia Tornado in Bangladesh in 1989, which killed approximately 1,300 people

Precipitation

Thunderstorms occur in the troposphere

Red sprites, blue jets and elves are upper atmospheric optical phenomena associated with thunderstorms

Rain gauge (also known as a udometer or a pluviometer) – a type of instrument used to gather and measure the amount of liquid precipitation (as opposed to solid precipitation that is measured by a snow gauge) over a set period of time

Hyetograph – a graphical representation of the distribution of rainfall over time

Drizzle – droplets of rain 0.2 – 0.5mm in diameter

Hail – precipitation in the form of spherical or irregular pellets of ice larger than 5 mm in diameter

Fog reduces visibility to less than 1 km, whereas mist reduces visibility to no less than 1 km

Acid rain – the most important gas which leads to acidification is sulphur dioxide. Emissions of nitrogen oxides which are oxidized to form nitric acid are of increasing importance

Virga – an observable shaft of precipitation that falls from a cloud but evaporates before reaching the ground

Graupel – also known as soft hail or snow pellets

Isohyet – a line joining points of equal precipitation

Thundersnow – also known as a winter thunderstorm or a thunder snowstorm, is an unusual kind of thunderstorm with snow falling as the primary precipitation instead of rain

Buys-Ballot's law may be expressed as follows: In the Northern Hemisphere, stand with your back to the wind; the low pressure area will be on your left. In other words, wind travels counterclockwise around low pressure zones in the Northern Hemisphere

Coriolis Effect is the apparent deflection of objects from a straight path if the objects are viewed from a rotating frame of reference. One of the most notable examples is the deflection of winds moving along the surface of the Earth to the right of the direction of travel in the Northern hemisphere and to the left of the direction of travel in the Southern hemisphere. This effect is caused by the rotation of the Earth

Milankovitch cycles are the collective effect of changes in the Earth's movements upon its climate. The eccentricity, axial tilt, and precession of the Earth's orbit vary in several patterns, resulting in 100,000 year ice age cycles of the Quaternary glaciation over the last few million years. Named after Serbian civil engineer and mathematician Milutin Milanković

Keeling Curve is a graph showing the variation in concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide since 1958. It is based on continuous measurements taken at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii under the supervision of Charles David Keeling. Keeling's measurements showed the first significant evidence of rapidly increasing carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere

El Nino-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a global coupled ocean-atmosphere phenomenon. The Pacific Ocean signatures, El Nino and La Nina are important temperature fluctuations in surface waters of the tropical Eastern Pacific Ocean. The name El Nino, from the Spanish for ‘the little boy’, refers to the Christ child, because the phenomenon is usually noticed around Christmas time in the Pacific Ocean off the west coast of South America. The warming brings nutrient-poor tropical water southward along the west coast of South America in major events that recur at intervals of 3 to 7 years. La Nina means ‘the little girl’, and is a phenomenon characterized by unusually cold ocean temperatures in the eastern Equatorial Pacific.Their effect on climate in the southern hemisphere is profound. These effects were first described in 1923 by Sir Gilbert Thomas Walker

Southern Oscillation – the atmospheric component of El Nino. It is an oscillation in air pressure between the tropical eastern and the western Pacific Ocean waters

North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) is a climatic phenomenon in the North Atlantic Ocean of fluctuations in the difference of atmospheric pressure at sea-level between the Icelandic low and the Azores high

Lightning is attracted to the layer of perspiration on the human body

Catatumbo Lightning is an atmospheric phenomenon in Venezuela. It occurs strictly in an area located over the mouth of the Catatumbo River where it empties into Lake Maracaibo. The frequent, powerful flashes of lightning over this relatively small area are considered to be the world's largest single generator of tropospheric ozone

Global dimming – the gradual reduction in the amount of global direct irradiance at the Earth's surface

Stevenson Screen – an enclosure to shield meteorological instruments against precipitation and direct heat radiation from outside sources

Crepuscular rays (also known as God Rays) are rays of sunlight that appear to radiate from a single point in the sky

Stationary front – a boundary between two different air masses, neither of which is strong enough to replace the other. On a weather map, this is shown by an inter-playing series of blue spikes pointing one direction and red domes pointing the other

Alberta clipper (also known as a Canadian Clipper) is a fast moving low pressure area which generally affects the central provinces of Canada and parts of the Upper Midwest and Great Lakes regions of the United States

An urban heat island is a metropolitan area that is significantly warmer than its surrounding rural areas due to human activities

Glaciation

In 1840 Louis Agassiz and William Buckland visited the mountains of Scotland, and found in different locations clear evidence of ancient glacial action. The discovery was announced to the Geological Society of London

James Croll developed a theory of the effects of variations of the Earth's orbit on climate cycles. His idea was that decreases in winter sunlight would favour snow accumulation, and for the first time coupled this to the idea of a positive ice-albedo feedback to amplify the solar variations. He suggested that when orbital eccentricity is high, then winters will tend to be colder when earth is farther from the sun in that season and hence, that during periods of high orbital eccentricity, ice ages occur on 22,000 year cycles in each hemisphere, and alternate between southern and northern hemispheres, lasting approximately 10,000 years each

The ‘Parallel Roads’ of Glen Roy are lake terraces that formed along the shorelines of an ancient ice-dammed lake. The lake existed during a brief period (some 900 to 1100 years in duration) of climatic deterioration, during a much longer period of deglaciation, subsequent to the last main ice age. From a distance they resemble man-made roads running along the side of the Glen

Rannoch Moor was at the heart of the last significant icefield in the UK during the Loch Lomond Stadial at the end of the last ice age

An interglacial is a geological interval of warmer global average temperature that separates glacial periods within an ice age. The current Holocene interglacial has persisted since the end of the Pleistocene, about 11,400 years ago

A stadial is a time of colder temperatures during an interglacial period separating the glacial periods of an ice age. A stadial is of insufficient duration or intensity to be considered a glacial period. Notable stadials include the Older and Younger Dryas events and the Little Ice Age

Younger Dryas stadial was a brief (approximately 1300 ± 70 years) cold climate period at the end of the Pleistocene

Little Ice Age – a period of cooling occurring after a warmer North Atlantic era known as the Medieval Warm Period. While not a true ice age, the term was introduced into scientific literature by Francois Matthes in 1939. NASA defines the term as a cold period between 1550 and 1850

An interstadial is a warmer period during a glacial period of an ice age. An interstadial is of insufficient duration or intensity to be considered an interglacial. Generally, interstadials endure for less than 10,000 years and interglacials for more than 10,000 years. The Eemian Stage, which lasted from c. 130,000 – 75,000 years ago, was the last interglacial prior to the present Holocene epoch

Heinrich events, first described by marine geologist Hartmut Heinrich, occurred during the last glacial period, or ice age. During such events, armadas of icebergs broke off from glaciers and traversed the North Atlantic

Lake Agassiz was an immense glacial lake located in the centre of North America. Fed by glacial runoff at the end of the last glacial period, its area was larger than all of the modern Great Lakes combined. Climatologists believe that a major outbreak of Lake Agassiz about 13,000 years ago drained through the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence River into the Atlantic Ocean. This may be the cause of the Younger Dryas stadial. The last major shift in drainage occurred about 8400 years ago, when the lake took up its current watershed, draining into Hudson Bay

The current ice age, the Pliocene-Quaternary glaciation, started about 2.58 million years ago during the late Pliocene, when the spread of ice sheets in the Northern Hemisphere began

Glaciations – Wurm (Wisconsinian), Riss (Illinoian), Mindel (Kansan), Gunz (Nebraskan)

Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) refers to the time of maximum extent of the ice sheets during the last glaciation (Wurm), approximately 20,000 years ago

Wurm glaciation is known as Devensian glaciation in Britain

The Younger Dryas impact event or Clovis comet hypothesis refers to the hypothesized large air burst or earth impact of objects from outer space that initiated the Younger Dryas cold spell about 10,900 BC. The theory proposes that an air burst and/or earth impact set vast areas of the North American continent on fire, causing the extinction of most of the large animals in North America and the demise of the North American Clovis culture at the end of the last glacial period

Svante Arrhenius developed a theory to explain the ice ages, and in 1896 he was the first scientist to attempt to calculate how changes in the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere could alter the surface temperature through the greenhouse effect

Arete – a thin, almost knife-like, ridge of rock which is typically formed when two glaciers erode parallel U-shaped valleys. The arete is a thin ridge of rock that is left separating the two valleys

Bergschrund – a split or crevasse in the ice of a glacier, where the glacier detaches itself from the mountain's rock

Cirque – a valley head, formed at the head of a valley glacier by erosion. Also known as cwm or corrie

Drumlin – elongated whale-shaped hill formed by glacial action

Erratic – a piece of rock that differs from the size and type of rock native to the area in which it rests. Erratics are carried by glacial ice

Hanging valley – a tributary valley with the floor at a higher relief than the main channel into which it flows. They are most commonly associated with U-shaped valleys when a tributary glacier flows into a glacier of larger volume

Kettle hole – a shallow, sediment-filled body of water formed by retreating glaciers

Ice shelf – a thick floating platform of ice that forms where a glacier or ice sheet flows down to a coastline and onto the ocean surface. Ice shelves are only found in Antarctica, Greenland and Canada. The boundary between the floating ice shelf and the grounded (resting on bedrock) ice that feeds it is called the grounding line

Meltwater – comes from glaciers that have receded over time. Often, there will be rivers flowing through glaciers into lakes. These brilliantly blue lakes get their colour from ‘rock flour’, sediment that has been transported through the rivers to the lakes

Moulin or glacier mill – a narrow, tubular chute, hole or crevasse through which water enters a glacier from the surface

Moraine – a glacially formed accumulation of unconsolidated glacial debris (soil and rock). Types of moraine – lateral, terminal, medial, ground, washboard

Neve – the upper part of a glacier, above the limit or perpetual snow

Nunatak – an exposed, often rocky element of a ridge, mountain, or peak not covered with ice or snow within (or at the edge of) an ice field or glacier

Periglaciation – processes that occur at the edges of glacial areas

Pingo – a periglacial mound of earth-covered ice found in the Arctic and subarctic

Proglacial lake – a lake formed either by the damming action of a moraine or ice dam during the retreat of a melting glacier, or by meltwater trapped against an ice sheet due to isostatic depression of the crust around the ice

Ribbon lake – a long and narrow, finger-shaped lake, usually found in a glacial trough

Roche moutonnée (or sheepback) – a rock formation created by the passing of a glacier. The passage of glacier ice over underlying bedrock often results in asymmetric erosional forms as a result of abrasion on the stoss (upstream) side of the rock and plucking on the lee (downstream) side

Serac – a block or column of ice formed by intersecting crevasses on a glacier

Striation – a scratch or gouge cut into bedrock by glacial abrasion

Tarn – a mountain lake or pool, formed in a cirque excavated by a glacier

Geological timescales

The largest defined unit of time is the Eon. Eons are divided into Eras, which are in turn divided into Periods, Epochs and Stages (or Ages)

Current eon – Phanerozoic, started 545 Million Years Ago (MYA)

Current era – Cenozoic

Current period – Quaternary

Current epoch – Holocene

Precambrian (also known as Cryptozoic) – an informal name for the span of time before the current Phanerozoic Eon, and is divided into the following eons – Hadean, Achaean and Proterozoic

The first billion years of the Earth’s existence is known as the Hadean period, as the planet was still hot and molten

Neoproterozoic Era is the unit of geologic time from 1000 to 542 MYA. The terminal Era of the formal Proterozoic Eon (or the informal ‘Precambrian’), it is further subdivided into the Tonian, Cryogenian, and Ediacaran Periods

The Snowball Earth hypothesis suggests that the Earth was entirely covered by ice during parts of the Cryogenian period, from 790 to 630 MYA. It was developed to explain sedimentary deposits generally regarded as of glacial origin at seemingly tropical latitudes. The term ‘Snowball Earth’ was coined by Joseph Kirschvink. Caused by reduced CO2 levels due to weathering. Ended by volcanoes breaking through ice sheet leading to increased CO2 levels

Palaeozoic Era (600 to 250 MYA) – means ‘ancient life’

Palaeozoic Era is divided into six periods –

1.Cambrian – ‘Cambrian explosion’ was the geologically sudden appearance of complex multi-cellular macroscopic organisms between roughly 542 and 530 MYA

2.Ordovician – named after the Welsh tribe of the Ordovices

3.Silurian – named after the Celtic tribe Silures. Vascular plants evolved in the Silurian

4.Devonian – named after Devon. Known as the ‘age of fishes’. Amphibians first appeared

5.Carboniferous – divided into Upper (Pennsylvanian) and Lower (Mississippian)

During the Carboniferous period, the atmospheric concentration of oxygen reached 35%, allowing insects to grow to much larger sizes than they are today

6.Permian – named after the kingdom of Permia in modern-day Russia by Scottish geologist Roderick Murchison in 1841

Permian–Triassic (P–Tr) extinction event, informally known as the Great Dying, was an extinction event that occurred 251.4 MYA, forming the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods. It was the Earth's most severe extinction event, with up to 96 percent of all marine species and 70 percent of terrestrial vertebrate species becoming extinct

Mesozoic Era (250 to 65 MYA) – means ‘middle life’. Divided into three periods –

1.Triassic (250 to 200 MYA) – time of the first dinosaurs

2.Jurassic (200 to 145 MYA) – time of giant herbivores

3.Cretaceous (145 to 65 MYA) – time of dinosaur domination of land. Longest geological period. First flowering plants developed

Tertiary (65 to 1.8 MYA) – began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event, at the start of the Cenozoic Era, spanning to the beginning of the most recent Ice Age, at the end of the Pliocene epoch. The Tertiary is not presently recognized as a formal unit by the International Commission on Stratigraphy, its traditional span being divided between the Paleogene and Neogene Periods

Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event, which occurred approximately 65.5 MYA, was a large-scale mass extinction of animal and plant species in a geologically short period of time. Widely known as the K–T extinction event, it is associated with a geological signature known as the K–T boundary, usually a thin band of sedimentation found in various parts of the world

Walter Alvarez proposed that large amounts of iridium in geological layers at the K-T boundary was evidence that a meteor impact caused the extinction of the dinosaurs. Son of experimental physicist Luis Walter Alvarez

Cenozoic Era (65 MYA – present) – means ‘recent life’

Cenozoic is divided into the Paleogene, Neogene and Quaternary periods

1.Paleogene is divided into three epochs –

1a.Palaeocene – demise of non-avian dinosaurs

Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), alternatively Eocene thermal maximum 1 (ETM1) refers to a climate event that began at the temporal boundary between the Paleocene and Eocene epochs. The absolute age and duration of the event remain uncertain, but are close to 55.8 MYA. The PETM is characterized by extreme changes on Earth’s surface, whereby global temperatures rose by about 6 °C

Eocene Thermal Maximum 2 (ETM-2), also called H-1 or the Elmo event, was a transient period of global warming that occurred 53.7 MYA

1b.Eocene – includes the warmest climate in the Cenozoic Era

1c.Oligocene – rise of true carnivores

2.Neogene is divided into two epochs –

2a.Miocene – grasses and grazing mammals develop

2b.Pliocene – first modern animals

3.Quaternary is divided into two epochs –

3a.Pleistocene (2.588 million – 12,000 years ago)

3b.Holocene (began 12,000 years ago) – start of the Holocene marks the transition between the Paleolithic and Mesolithic periods in the development of humans

Holocene extinction, sometimes called the Sixth Extinction, is a name proposed to describe the currently ongoing extinction event of species during the present Holocene epoch mainly due to human activity

Anthropocene – the most recent period in the Earth's history, starting in the 18th century when the activities of the human race first began to have a significant global impact on the Earth's climate and ecosystems. The term was coined in 2000 by the Nobel Prize winning scientist Paul Crutzen, who regards the influence of mankind on the Earth in recent centuries as so significant as to constitute a new geological era

The classical ‘Big Five’ mass extinctions identified by Jack Sepkoski and David M. Raup in their 1982 paper are widely agreed upon as some of the most significant: End Ordovician, Late Devonian, End Permian, End Triassic, and End Cretaceous

Rocks

Rock cycle – the dynamic transitions through geologic time among the three main rock types: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary. Each of the types of rocks are altered or destroyed when it is forced out of its equilibrium conditions

Stratigraphy studies rock layers and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks

Biostratigraphy focuses on correlating and assigning relative ages of rock strata by using the fossil assemblages contained within them

Lithostratigraphy focuses upon geochronology, comparative geology, and petrology

Diagenesis – all the chemical, physical, and biological changes, including cementation, undergone by a sediment after its initial deposition, exclusive of surface weathering

Lithification – the process in which sediments compact under pressure, and gradually become solid rock

Cryptocrystalline – a rock texture made up of such minute crystals that its crystalline nature is only vaguely revealed even microscopically in thin section by transmitted polarized light

Regolith – the layer of loose rock resting on bedrock

Mafic – a silicate mineral or rock that is rich in magnesium and iron

Ultramafic – rocks with a very low silica content (less than 45%), generally >18% magnesium oxide

Breccia – a rock composed of broken fragments of minerals or rock cemented together by a fine-grained matrix

Emery (or corundite) – a dark granular rock used to make abrasive powder. It largely consists of the mineral corundum (aluminium oxide)

TAS (Total Alkali Silica) classification can be used to assign names to many common types of volcanic rocks based upon the relationships between the combined alkali content and the silica content

Geologists categorize faults into three main groups based on the sense of slip: a fault where the relative movement (or slip) on the fault plane is approximately vertical is known as a dip-slip fault; where the slip is approximately horizontal, the fault is known as a or strike-slip fault; an oblique-slip fault has non-zero components of both strike and dip slip

Anticlines are favored locations for oil and natural gas drilling; the low density of petroleum causes it to buoyantly migrate upward to the highest parts of the fold, until stopped by a low-permeability barrier such as an impermeable stratum or fault zone. Examples of low-permeability seals that contain the hydrocarbons, oil and gas, in the ground include shale, limestone, sandstone, and even salt domes

Wentworth scale – boulder (largest), cobble, pebble, gravel, sand, silt, clay

Aquifer – an underground layer of water-bearing permeable rock from which groundwater can be extracted using a water well

Artesian aquifer – an aquifer containing groundwater under positive pressure. This causes the water level in a well to rise to a point where hydrostatic equilibrium has been reached. This type of well is called an artesian well

Angle of repose – the steepest angle of descent or dip of the slope relative to the horizontal plane when material on the slope face is on the verge of sliding

Creep – the slow downward progression of rock and soil down a low grade slope

Weathering – the breaking down of rocks, soil and minerals as well as artificial materials through contact with the Earth's atmosphere, biota and waters. Weathering occurs in situ, and should not be confused with erosion, which involves the movement of rocks and minerals by agents such as water, ice, snow, wind, waves and gravity and then being transported and deposited in other locations. Two important classifications of weathering processes exist – physical (or mechanical) and chemical weathering

Mechanical weathering can be the result of pressure release, known as unloading, e.g. ice melts leading to an underlying volcano erupting

Igneous

Igneous – any of various crystalline or glassy, non-crystalline rocks formed by the cooling and solidification of magma. Broadly divided into extrusive (volcanic) rocks and intrusive rocks. Extrusive rocks form from lava on Earth’s surface, while intrusive rocks form underground, from magma

Felsic – igneous rocks that are relatively rich in elements that form feldspar and quartz

Pluton – a body of intrusive igneous rock (called a plutonic rock) that is crystallized from magma slowly cooling below the surface of the Earth. Plutons include batholiths, dikes, and sills

Batholith – a very large body of igneous rock, usually granite, which has been exposed by erosion of the overlying rock

Aphanitic igneous rocks are so fine-grained that their component mineral crystals are not detectable by the unaided eye (as opposed to phaneritic igneous rocks, where the minerals are visible to the unaided eye)

Basalt – a common extrusive rock formed from the rapid cooling of basaltic lava. By definition, basalt is an aphanitic igneous rock with less than 20% quartz by volume. Basalt is the most common rock forming the oceanic crust

Rhyolite – an igneous volcanic (extrusive) rock of felsic composition. Rhyolite can be considered as the extrusive equivalent to granite

Pumice – contains small crystals of feldspar in a glassy matrix. Formed from frothy lava

Obsidian – a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed as an extrusive igneous rock

Perlite – an amorphous volcanic glass that has a relatively high water content, typically formed by the hydration of obsidian

Andesite – an extrusive volcanic rock common in subduction zones

Granite – a common and widely occurring type of intrusive, felsic, igneous rock. Typically consists of quartz, feldspar, and mica. Granites are usually medium to coarsely crystalline, occasionally with some individual crystals larger than the groundmass forming a rock known as porphyry. Granite has at least 20% quartz by volume. Granite differs from granodiorite in that at least 35% of the feldspar in granite is alkali feldspar as opposed to plagioclase; it is the alkali feldspar that gives many granites a distinctive pink colour

Granodiorite – an intrusive igneous rock similar to granite, but containing more plagioclase than orthoclase-type feldspar. The most common intrusive igneous rock in the continental crust

Dolerite – typically occurs in sills and dykes

Diorite – contains very little quartz. Used for ornamental purposes in ancient Egypt

Peridotite – an ultramafic coarse-grained rock, consisting mostly of the minerals olivine and pyroxene. Main rock of the Earth’s upper mantle

Gabbro – a large group of dark, coarse-grained, intrusive mafic igneous rocks chemically equivalent to basalt. The rocks are intrusive, formed when molten magma is trapped beneath the Earth's surface and cools into a crystalline mass

Kimberlite – a type of ultramafic volcanic rock best known for sometimes containing diamonds. It is named after the town of Kimberley in South Africa, where the discovery of a diamond in 1871 spawned a diamond rush. Kimberlite occurs in the Earth's crust in vertical structures known as kimberlite pipes

Metamorphic

Metamorphic – the process by which rocks are altered in composition, texture, or internal structure by extreme heat and pressure

Recrystallization – the change in the particle size of the rock during the process of metamorphism

Foliation – the layering within metamorphic rocks

Contact metamorphism – the changes that take place when magma is injected into the surrounding solid rock

Regional metamorphism – also known as dynamic metamorphism, is the name given to changes in great masses of rock over a wide area

Marmorosis – metamorphism of limestone into marble

Schist – rock with medium to large grains of mica flakes in a preferred orientation. The names of various schists are derived from their mineral constituents. Schists rich in mica are called mica schists, and include biotite or muscovite. Some schists are named for their prominent mineral constituents, e.g. garnet schist

Slate – a fine-grained, foliated, metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through regional metamorphism

Hornfels – a series of contact metamorphic rocks that have been baked by the heat of intrusive igneous masses and have been rendered massive, hard, splintery, and in some cases exceedingly tough and durable. Also known as whetstones

Gneiss – formed at high temperatures and pressures by regional metamorphism. Characterized by alternating darker and lighter coloured bands, called ‘gneissic banding’

Most of the Outer Hebrides have bedrock formed from Lewisian gneiss. This bedrock contains rocks that are among the oldest in Europe and indeed the world

Serpentinite – composed of one or more serpentine group minerals. Found in convergence zones between tectonic plates

Marble – a non-foliated metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite

Purbeck Marble is a fossiliferous limestone quarried in the Isle of Purbeck. It is one of many kinds of Purbeck Limestone, deposited in the late Jurassic or early Cretaceous periods

Soapstone – a metamorphic rock composed predominantly of talc

Jade is an ornamental stone. The term jade is applied to two different metamorphic rocks that are made up of different silicate minerals – nephrite and jadeite

Sedimentary

Sedimentary – resembling or containing or formed by the accumulation of sediment

Sedimentary rocks are classified into three groups –

1.Clastic – composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing rock. The term clastic is used with reference to sedimentary rocks as well as to particles in sediment transport. Subdivided into –

a. Conglomerates and breccias –

Conglomerates are dominantly composed of rounded gravel and breccias are composed of dominantly angular gravel

b. Sandstones –

Sandstone – most sandstone is composed of quartz and/or feldspar because these are the most common minerals in the Earth's crust. Like sand, sandstone may be any colour

Sandstones are classified using the Dott scheme. Six sandstone names are possible using descriptors for grain composition (quartz-, feldspathic-, and lithic-) and amount of matrix (wacke or arenite)

Gritstone or grit – a hard, coarse-grained, siliceous sandstone. Millstone Grit is an informal term for a succession of gritstones which are to be found in the Peak District and Pennines

Greywacke – a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness, dark colour, and poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments

c. Mudrocks –

Shale – composed of mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especially quartz and calcite. A fine-grained, layered rock

Claystone – composed primarily of clay-sized particles

Marl or marlstone – a calcium carbonate or lime-rich mud or mudstone which contains variable amounts of clays and silt. Midway between clay and limestone in hardness

Mudstone (also called mudrock) – a fine grained sedimentary rock whose original constituents were clays or muds

Siltstone – a sedimentary rock which has a grain size in the silt range, finer than sandstone and coarser than claystones

2. Chemical – form when mineral constituents in solution become supersaturated and inorganically precipitate

Oolitic limestone – composed of ooliths – small, rounded, concentrically banded sedimentary grains rolled by sea bed currents and cemented by carbonate mud

3. Biochemical – created when organisms use materials dissolved in air or water to build their tissue

Limestone – a sedimentary rock composed largely of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Many limestones are composed from skeletal fragments of marine organisms such as coral or foraminifera

Chalk – a soft, white, porous sedimentary rock, a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite. Calcite is calcium carbonate

Travertine – a form of limestone deposited by mineral springs, especially hot springs

Tufa – a variety of limestone, formed by the precipitation of carbonate minerals from ambient temperature water bodies

Two major classification schemes, the Folk and the Dunham, are used for identifying limestone and carbonate rocks

Dolostone or dolomite rock – a carbonate rock that contains a high percentage of the mineral dolomite. Most dolostone formed as a magnesium replacement of limestone or lime mud prior to lithification

Anchracite – purest form of coal. Black and shiny

Bituminous coal – most abundant type of coal. Lower carbon content than anthracite

Lignite – brown coal with lower carbon content than bituminous coal

Sedimentary rocks can be subdivided into compositional groups based on their mineralogy –

Siliciclastic – dominantly composed of silicate minerals, e.g. sandstone

Carbonate – e.g. limestone and dolostone

Evaporite – composed of minerals formed from the evaporation of water, e.g. halite and gypsum

Organic-rich – e.g. coal, oil shale

Siliceous – almost entirely composed of silica, e.g. chert, opal. Diatomaceous earth, also known as diatomite or kieselguhr, is a naturally occurring, soft, siliceous sedimentary rock that is easily crumbled into a fine white powder. It consists of fossilized remains of diatoms, a type of hard-shelled algae. It is used as a filtration aid

Iron-rich – composed of >15% iron, e.g. ironstone

Phosphatic – composed of phosphate minerals and contain more than 6.5% phosphorus

Red beds – sedimentary rocks which typically consist of sandstone, siltstone, and shale that are predominantly red in colour due to the presence of ferric oxides

Varve – an annual layer of sediment or sedimentary rock

Minerals

Mineral – a naturally occurring solid chemical substance that is formed through geological processes and that has a characteristic chemical composition, a highly ordered atomic structure, and specific physical properties. To be classified as a true mineral, a substance must be a solid and have a crystalline structure

Sulphides – a large group of minerals in which sulphur is combined with one or more metals –

Cinnabar – mercury sulphide. During the Roman Empire it was mined both as a pigment and for its mercury content. To produce liquid mercury (quicksilver), crushed cinnabar ore is roasted in rotary furnaces. Vermilion is an opaque orangish red pigment, similar to scarlet. As a naturally occurring mineral pigment, it is known as cinnabar

Stibnite – a sulphide of antimony

Galena – chief ore of lead. Galena is the natural mineral form of lead sulphide

Sphalerite – a sulphide of zinc with variable iron content. The most heavily-mined zinc- containing ore

Acanthite – silver suplhide. Main ore of silver

Orpiment – arsenic sulphide. Latin for ‘golden paint’. Used as a pigment

Molybdenite – molybdenum sulphide

Arsenopyrite – sulphide of arsenic and iron. Principal ore of arsenic

Stannite – a sulphide of copper, iron, and tin. Mined for tin

Pendlandite – nickel and iron sulphide. Found in igneous rocks. Important source of nickel

Pyrite – iron suphide known as ‘fool’s good’. Most common of all sulphide minerals

Chalcocite – copper sulphide. Mined for copper ores

Chalcopyrite – a copper iron sulphide

Sulphosalts – a group of rare minerals. Sulphur is combined with a metallic element and a semimetal (often arsenic or antimony)

Tetrahedrite – a copper antimony sulphosalt mineral, named after its tetrahedron-shaped crystals

Oxides – compounds of oxygen and other elements –

Cuprite – copper oxide

Ilmenite – iron titanium oxide. Principal ore of titanium

Uraninite – uranium oxide. Main ore of uranium. Contains radium. Also known as pitchblende

Cassiterite – ore of tin. Most important source of tin today

Corundum – (from Tamil kurundam) is a crystalline form of aluminium oxide with traces of iron, titanium and chromium. Due to corundum's hardness (9.0 Mohs), it is commonly used as an abrasive in machining. Corundum is naturally clear, but can have different colours when impurities are present. Transparent specimens are used as gems

Sapphire – a variety of corundum. Amounts of other elements such as iron, titanium, chromium, copper, or magnesium can give corundum blue, yellow, purple, orange, or a greenish colour. Chromium impurities in corundum yield a pink or red tint, the latter being called a ruby

Chromite – iron chromium oxide. Important source of chromium

Magnetite – iron oxide. The most magnetic of all the naturally occurring minerals on Earth. Naturally magnetized pieces of magnetite, called lodestone, will attract small pieces of iron, and this was how ancient man first discovered the property of magnetism. Lodestone was used as an early form of magnetic compass

Haematite – the mineral form of iron oxide. Mined extensively for iron

Pyrolusite – manganese oxide. Primary ore of manganese

Rutile – composed primarily of titanium dioxide. A source of titanium

Chrysoberyl – beryllium aluminium oxide. A prized gemstone

Tantalite – the primary source of tantalum

Hydroxides – compounds of a metallic element and the hydroxyl radical (OH)

Gibbsite – one of the mineral forms of aluminium hydroxide. Gibbsite is an important ore of aluminium in that it is one of three main phases that make up bauxite

Bauxite – an assemblage of aluminium hydroxides and iron hydroxides

Halides – compounds of a metallic element and a halogen element

Fluorite – (also called fluorspar) is composed of calcium fluoride. Used for making hydrofluoric acid. Blue John is a variety of fluorspar

Sylvite – potassium chloride

Halite – sodium chloride. Common salt

Carbonates – compounds of metallic or semimetallic elements combined with the carbonate radical (CO3). Over 70 carbonate minerals are known, but calcite, dolomite, and siderite account for most of the carbonate in Earth’s crust

Calcite – calcium carbonate. Occurs as limestone or marble

Dolomite – calcium magnesium carbonate. Widespread in altered limestones

Siderite – a mineral composed of iron carbonate. May occur in botryoidal form

Witherite – carbonate of barium

Magnesite – magnesium carbonate

Strontianite – strontium carbonate

Cerussite – most common lead ore after galena

Azurite – a hydrous copper carbonate

Aragonite – one of the two common, naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate (the other form is calcite)

Malachite – copper carbonate. Malachite often results from weathering of copper ores and has a vibrant green colour. Malachite releases copper when heated

Borates – compounds of metallic elements combined with the borate radical (BO3)

Borax – also known as sodium borate. Composed of white crystals. A component of many detergents, cosmetics, and enamel glazes

Nitrates – compounds of metallic elements combined with the nitrate radical (NO2)

Nitratite – sodium nitrate. Typically occurs as crusts on the ground surface in arid regions. Known as ‘Chile saltpetre’

Sulphates – compounds of metals joined to the sulphate radical (SO4)

Anhydrite – anhydrous calcium sulphate. Alters to gypsum in humid conditions

Gypsum – hydrated calcium sulphate. Makes plaster of Paris

Epsomite – hydrated magnesium sulphate. Source of Epsom salts

Celestine – strontium sulphate

Anglesite – a lead sulphate mineral. It occurs as an oxidation product of primary lead sulphide ore, galena. Discovered on Anglesey

Barite – barium sulphate. Most common barium mineral

Mirabilite – sodium sulphate. Known as Glauber’s salt

Phosphates – compounds of metals joined to the phosphate radical (PO4)

Turquoise – hydrated phosphate of copper and aluminium

Apatite – calcium phosphate

Silicates – any of a large group of minerals, forming over 90 percent of the earth's crust that consists of silicon, oxygen, and one or more metals (and sometimes hydrogen). Silicates contain the silicate ion (SiO4)

Silicates are subdivided into 6 groups based on the arrangement of the silica tetrahedral –

1. Neosilicates (form as isolated tetrahedra)

Garnet group – found in many colours

Andradite is a species of the garnet group. Andradite includes three varieties: Melanite (black in colour), Demantoid (vivid green in colour), and Topazolite (yellow-green in colour)

Olivine group – a magnesium iron silicate. Also known as peridot and chrysolite

Topaz – a silicate mineral of aluminium and fluorine. Pure topaz is colourless and transparent but is usually tinted by impurities

Zircon – zirconium silicate. Main source of zirconium. Zircon contains amounts of uranium and thorium and can be dated using modern analytical techniques

2. Sorosilicates (occur in pairs)

Vesunianite – first discovered adjacent to lavas on Mount Vesuvius

Tanzanite – the blue/purple variety of the mineral zoisite discovered in Northern Tanzania in 1967. It is used as a gemstone

3. Cyclosilicates (form as rings of tetrahedra)

Tourmaline – a group of 11 hydrous boron silicate minerals. The gemstone comes in a wide variety of colours

Beryl – a beryllium aluminium silicate mineral

Aquamarine is a blue or turquoise variety of beryl

Emerald refers to green beryl, coloured by trace amounts of chromium and sometimes vanadium

Goshenite, morganite, bixbite, heliodor – varieties of beryl

4. Inosilicates (form as chains of tetrahedra)

Amphibole – group of generally dark-coloured minerals, forming prism or needlelike crystals

Hornblende – is not a recognized mineral in its own right, but the name is used as a general or field term, to refer to a dark amphibole. Hornblende is a common constituent of many igneous and metamorphic rocks

Pyroxene – group of important rock-forming silicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks

Augite – the most common pyroxene

5. Phyllosilicates (form as sheets of tetrahedra)

Mica group – includes several closely related materials having close to perfect basal cleavage

Muscovite – (also known as common mica, isinglass, or potash mica) is a mineral of aluminium and potassium

Chrysotile – or white asbestos is the most commonly encountered form of asbestos

Clay minerals – hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates

Talc – hydrated magnesium silicate

Kaolinite – silicate of aluminium. It is mined as kaolin

Serpentine group – greenish, brownish, or spotted minerals commonly found in serpentinite rocks. Used as a source of magnesium and asbestos, and as a decorative stone. The name is thought to come from the greenish colour being that of a serpent

6. Tectosilicates (have a three-dimensional network of tetrahedra)

Quartz is the second most abundant mineral in the Earth's continental crust, after feldspar. It is made up of a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall formula SiO2. There are many different varieties of quartz, several of which are semi-precious gemstones

Two forms of quartz exist, alpha-quartz which is stable from the low end of the temperature range up to 573°C and beta-quartz, the high temperature stable form from 573°C to 867°C

Rock crystal – pure quartz. Transparent and colourless. Used as a carving material since ancient times

Citrine – a variety of quartz whose colour ranges from a pale yellow to brown

Rose quartz – a type of quartz which exhibits a pale pink to rose red hue

Amethyst – purple variety of quartz, prized since ancient times

Smoky quartz – a translucent version of quartz. Ranges in clarity from almost complete transparency to a brownish-gray crystal that is almost opaque. Cairngorm is a variety of smoky quartz crystal found in the Cairngorm Mountains

Milky quartz – milky white variety of quartz. Very common

Jasper – a form of chalcedony (microcrystalline quartz). An opaque impure variety of silica, usually red, yellow, brown or green in colour

Agate – a form of chalcedony characterized by its fineness of grain, brightness of colour, and concentric colour bands caused by impurities

Onyx – a banded variety of chalcedony

Feldspar – a group of rock-forming minerals which make up as much as 60% of the Earth's crust. Feldspars crystallize from magma in both intrusive and extrusive rocks, and they can also occur as compact minerals, as veins, and are also present in many types of metamorphic rock

Lazurite – main mineral in lapis lazuli gems

Plagioclase – series of feldspars ranging from albite to anorthite. Includes andesine and oligoclase

Microcline – potassium aluminosilicate. A common alkali feldspar

Zeolites – hydrated aluminosilicate minerals

Orthoclase – a tectosilicate mineral which forms igneous rock. The name is from the Greek for ‘straight fracture’ because its two cleavage planes are at right angles to each other. Alternate names are alkali feldspar and potassium feldspar

Flint is a hard, sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as a variety of chert. It occurs chiefly as nodules and masses in sedimentary rocks, such as chalks and limestones

Alabaster – a name applied to varieties of two distinct minerals, when used as a material: gypsum and calcite

Mineraloid – a mineral-like substance that does not demonstrate crystallinity

Fulgurite – a silica glass mineraloid formed when sand is fused by the energy of a lightning strike

Opal is a hydrated amorphous form of silica and is a mineraloid

Fire, Girasol, Peruvian – varieties of opal

Inclusion – any material that is trapped inside a mineral during its formation

Sclerometer – (from the Ancient Greek skleros meaning ‘hard’) is a mineralogist's instrument used to measure the hardness of materials

Mohs scale of mineral hardness characterizes the scratch resistance of various minerals through the ability of a harder material to scratch a softer material. It was created in 1812 by the German geologist and mineralogist Friedrich Mohs. Ranges from 1 (talc) to 10 (diamond)

| Mohs hardness | Mineral name |

| 1 | Talc |

| 2 | Gypsum |

| 3 | Calcite |

| 4 | Fluorite |

| 5 | Apatite |

| 6 | Orthoclase feldspar |

| 7 | Quartz |

| 8 | Topaz |

| 9 | Corundum |

| 10 | Diamond |

Biogeography

The term ecosystem was coined in 1930 by Roy Clapham to mean the combined physical and biological components of an environment. British ecologist Arthur Tansley later refined the term, describing it as ‘The whole system,… including not only the organism-complex, but also the whole complex of physical factors forming the environment’

Ecozone – the broadest biogeographic division of the Earth's land surface, based on distributional patterns of terrestrial organisms. Ecozones are divided into bioregions

Palearctic or Palaearctic is one of the eight ecozones constituting the Earth's surface. Physically, the Palearctic is the largest ecozone. It includes the terrestrial ecoregions of Europe, Asia north of the Himalaya foothills, northern Africa, and the northern and central parts of the Arabian Peninsula

Biomes – climatically and geographically defined as similar climatic conditions on the Earth, such as communities of plants, animals, and soil organisms. Biomes are a classification of globally similar areas, including ecosystems. A fundamental classification of biomes is: 1. Terrestrial (land) biomes (e.g. tundra, temperate forests)

2. Aquatic biomes (e.g. pond, coral reef)

Tundra – a biome where the tree growth is hindered by low temperatures and short growing seasons. The vegetation is composed of dwarf shrubs, sedges and grasses, mosses, and lichens

Taiga – also known as the boreal forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests

Taiga contains one-third of the trees on Earth

Endolithic biome – contains organisms that live inside rock, coral, animal shells, or in the pores between mineral grains of a rock. Many are extremophiles; living in places previously thought inhospitable to life

A cold seep (sometimes called a cold vent) is an area of the ocean floor where hydrogen sulfide, methane and other hydrocarbon-rich fluid seepage occurs, often in the form of a brine pool. Cold seeps constitute a biome supporting several endemic species, including tubeworms

Holdridge life zones system – a global bioclimatic scheme for the classification of land areas, based on precipitation, humidity and evapotranspiration

Koppen climate classification – is based on the concept that native vegetation is the best expression of climate. Thus, climate zone boundaries have been selected with vegetation distribution in mind. It combines average annual and monthly temperatures and precipitation, and the seasonality of precipitation. First published by German climatologist Wladimir Koppen in 1884

Koppen climate classification scheme divides climates into five main groups – A: Tropical/megathermal; B: Dry (arid and semiarid); C: Temperate/mesothermal; D: Continetal/microthermal; E: Polar

In 1953, Peveril Meigs divided desert regions on Earth into three categories according to the amount of precipitation they received. In this system, extremely arid lands have at least 12 consecutive months without rainfall, arid lands have less than 10 inches of annual rainfall, and semiarid lands have a mean annual precipitation of 10–20 inches

Badlands are a type of arid terrain with clay-rich soil that has been extensively eroded by wind and water

Montane is a biogeographic term which refers to highland areas located below the subalpine zone

Scrubland – known as chaparral in USA, fynbos in South Africa, maquis in France, and mattoral in Chile

Grasslands – known as pampas, prairie, savanna, steppe, and veldt

Tree line – the edge of the habitat at which trees are capable of growing. Beyond the tree line, they are unable to grow because of inappropriate environmental conditions (usually cold temperatures, insufficient air pressure, or lack of moisture). Some distinguish additionally a deeper timberline, where trees can develop trunks

Peripatry – organisms whose ranges are closely adjacent but do not overlap

Structure of the Earth

Lithosphere – crust and upper mantle of the earth

Asthenosphere – the highly viscous, mechanically weak and ductilely-deforming region of the upper mantle of the Earth. It lies below the lithosphere, at depths between 100 and 200 km. It is involved in plate tectonic movements and isostatic adjustments

Mesosphere – the mantle in the region under the lithosphere and the asthenosphere, but above the outer core

Mantle – the highly viscous layer between the crust and the outer core

The upper part of the mantle is composed mostly of peridotite, a rock denser than rocks common in the overlying crust. The boundary between the crust and mantle is conventionally placed at the Mohorovicic discontinuity, a boundary defined by a contrast in seismic velocity

Mantle region just above the core is called D″ (D double-prime)

Core–mantle boundary lies between the Earth's silicate mantle and its liquid iron-nickel outer core. This boundary is located at approximately 2900 km of depth beneath the Earth's surface. Also known as the Gutenberg discontinuity

Lehmann discontinuity was originally referred to the liquid-solid boundary between the outer and inner core of the Earth, was named in honour of seismologist Inge Lehmann, who proposed on the basis of seismic waves that the Earth had an inner core

Outer core – ocean of white-hot molten metal

Inner core – solid sphere of nickel and iron about 1220 km in radius

P-waves travel through solids, liquids and gases

Unlike the P-wave, the S-wave cannot travel through the molten outer core of the Earth, and this causes a shadow zone for S-waves opposite to where they originate

S-wave shadow shows that outer core is liquid

P-wave refraction pattern shows inner core is solid

The oceanic crust is 5 km to 10 km thick and is composed primarily of basalt, diabase, and gabbro. The continental crust is typically from 30 km to 50 km thick and is mostly composed of slightly less dense rocks than those of the oceanic crust. Some of these less dense rocks, such as granite, are common in the continental crust but rare to absent in the oceanic crust

Sial – the composition of the upper layer of the Earth's crust, namely rocks rich in silicates and aluminium minerals

Isostacy – the state of gravitational equilibrium between the earth's lithosphere and asthenosphere such that the tectonic plates ‘float’ at an elevation which depends on their thickness and density. When a certain area of lithosphere reaches the state of isostasy, it is said to be in isostatic equilibrium

Geoid – the shape that the surface of the oceans would take under the influence of Earth's gravitation and rotation alone, in the absence of other influences such as winds and tides

Iron catastrophe – while residual heat from the collision of the material that formed the Earth was significant, heating from radioactive materials in this mass further increased the temperature until a critical condition was reached, when the material was molten enough to allow movement. At this point, the denser iron and nickel, evenly distributed throughout the mass, sank to the centre of the planet to form the core. This large spinning mass of super-hot metal is responsible for the magnetosphere

Pole shift hypothesis suggests that there have been geologically rapid shifts in the relative positions of the modern-day geographic locations of the poles and the axis of rotation of the Earth, creating calamities such as floods and tectonic events. Charles Hapgood is the best remembered early proponent. In his books The Earth's Shifting Crust (1958) and Path of the Pole (1970). Hapgood speculated that the ice mass at one or both poles over-accumulates and destabilizes the Earth's rotational balance, causing slippage of all or much of Earth's outer crust around the Earth's core, which retains its axial orientation

Earth's polar regions are the areas of the globe surrounding the poles also known as frigid zones

Great Circle – a circle on the surface of a sphere that has the same circumference as the sphere, dividing the sphere into two equal hemispheres. On the Earth, the meridians are on great circles, and the equator is a great circle

Meridian – an imaginary line on the Earth's surface from the North Pole to the South Pole that connects all locations with a given longitude. The position of a point on the meridian is given by the latitude

The dynamo effect is a geophysical theory that explains the origin of the Earth's main magnetic field in terms of a self-exciting (or self-sustaining) dynamo

Geodesy – the scientific discipline that deals with the measurement and representation of the Earth, including its gravitational field

Geomagnetic reversal – based upon the study of lava flows of basalt throughout the world, it has been proposed that the Earth's magnetic field reverses at intervals, ranging from tens of thousands to many millions of years, with an average interval of approximately 300,000 years. However, the last such event, called the Brunhes–Matuyama reversal, is observed to have occurred some 780,000 years ago

Paleomagnetism – the fixed orientation of a rock's crystals, based on the Earth's magnetic field at the time of the rock's formation, that remains constant even when the magnetic field changes

An isoclinic line connects points of equal magnetic dip, and an aclinic line connects those where the magnetic dip is zero

Supercontinents

Supercontinent – a single landmass consisting of all the modern continents. The earliest known supercontinent was Vaalbara. Other supercontinents – Kenorland, Columbia, Rodinia and Pangaea

Rodinia existed between 1100 and 750 million years ago

De Toit coined the terms Laurasia and Gondwanaland

Gondwanaland and Laurasia were parts of the Pangaea supercontinent

The Tethys Ocean was a Mesozoic era ocean that existed between the continents of Gondwana (Southern Hemisphere) and Laurasia (Northern Hemisphere) before the opening of the Indian Ocean

Seed ferns known as glossopteridales arose in the Southern Hemisphere around the beginning of the Permian Period. Their distribution across several, now detached, landmasses led Eduard Suess, amongst others, to propose that the southern continents were once amalgamated into a single supercontinent – Gondwana

Pangaea is the name given to the supercontinent that is believed to have existed during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras, forming 300 million years ago and beginning to break up approximately 200 million years ago, before the component continents were separated into their current configuration by plate tectonics. The single enormous ocean which surrounded Pangaea was named Panthalassa. The name was first used by Alfred Wegener in 1920

When Pangaea began to rift around 200 million years ago, North America became part of Laurasia, before it separated from Eurasia as its own continent during the mid-Cretaceous period

Plate tectonics and continental drift

Tectonics – large-scale processes that take place within the earth’s crust

Plate tectonics – the theory that the earth's surface consists of plates, or large crustal slabs, whose constant motion explains continental drift and mountain building. The plates, which comprise the lithosphere, are floating on the moving molten rock (the asthenosphere) that lies beneath. The plates move as a result of convection currents which occur deep within the mantle. New crust (a mid-ocean ridge) is formed at the edges of the plates where rising convection currents bring up new material from the mantle

Depending on how they are defined, there are usually seven or eight major plates: African, Antarctic, Eurasian, North American, South American, Pacific, and Indo-Australian. The latter is sometimes subdivided into the Indian and Australian plates.

There are dozens of smaller plates, the seven largest of which are the Arabian, Caribbean, Juan de Fuca, Cocos, Nazca, Philippine Sea, and Scotia

African plate subducts beneath Eurasian plate

Cimmerian Plate is an ancient tectonic plate that comprises parts of present-day Anatolia, Iran, Afghanistan, Tibet, Indochina and Malaya regions. The Cimmerian Plate was formerly part of Pangaea

San Andreas fault where the Pacific and North American plates meet

Andes formed by Nazca plate pushing under South American plate

Himalayas were formed when India detached from Madagascar and moved northwards, a continental collision or orogeny along the convergent boundary between the Indo-Australian Plate and the Eurasian Plate

Craton – an old and stable part of the continental lithosphere. Having often survived cycles of merging and rifting of continents, cratons are generally found in the interiors of tectonic plates. Cratons contain diamond-bearing kimberlites

Laurentia is a large continental craton, which forms the ancient geological core of the North American continent. The formation of the Isthmus of Panama connected the continent to South America about three million years ago

Continental drift – theory advocated by Alfred Wegener in 1912

Subduction zone – an area on Earth where two tectonic plates meet and move towards one another, with one sliding underneath the other and moving down into the mantle